Funny poetry is a style of poetry in it’s own right, different from the many other types of more serious verse. A style of poetry is often called a genre (pronounced ZHAHN-ruh). Other styles, or genres, include love poetry, cowboy poetry, jump-rope rhymes, epic poetry (really, really long poems), and so on.

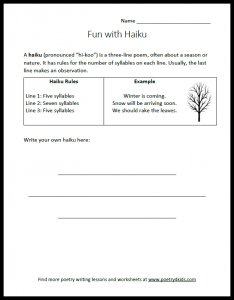

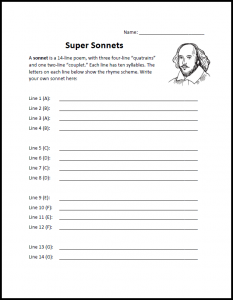

In addition to styles or genres of poetry, there are also poetic forms. A form is a particular type of poem with rules for how to write it. For example, you may have heard of a limerick or a haiku or an acrostic. These are poetic forms, and there are rules you can follow to write them.

In chapter 6 I discuss some of the traditional forms for funny poetry, such as limericks, clerihews, funny haiku, and so on. Each of these traditional forms has rules describing how many lines it must be, how many syllables it must contain, or what the poem can be about.

In this chapter, however, I’ll show you some of the common types of funny poetry that don’t have traditional names, and don’t have so many rules you have to follow. While there are as many types of funny poems as there are poets writing them, and any one poem may contain features of several different kinds, there are some types of funny poems you will see again and again. These include:

- Opposites / reverse / backward poems

- Tongue twisters

- Repetition poems

- List poems

- Updated nursery rhymes

Keep reading and you will see how you can create your own versions of these popular types of funny poetry.

Opposites/Reverse/Backward Poems

The opposite, reverse, or backward poem is a poem in which everything you normally expect is reversed. For example, if you wear your hat on your feet and your shoes on your head, you’ve got the beginnings of great a backward poem.

Backward poems are easy to write. All you have to do is make everything wrong. Purple bananas. Green stop signs. Three year-old parents. And so on. Let’s try a few. Here is the beginning of a poem about some backward people who live in a backward town.

The backward folks in backward town

live inside out and upside down.

They work all night and sleep all day.

They love to work and hate to play.

The parents there are three years old.

They save their trash and dump their gold.

They fly their cars and stand on chairs.

They comb their teeth and floss their hairs.

Now it’s your turn. See if you can write another stanza about the backward folks in backward town. What else do they do backward? Do they watch TV by turning it off? Do they cook dinner by putting it in the freezer? You decide.

Here’s another one.

My name is Mr. Backward.

I do things in reverse.

I’m happy when I’m crying.

I’m better when I’m worse.

My shoes are on my shoulders.

My hat is on my toes.

I smell things with my fingers.

I write things with my nose.

Now you try it. Tell me more about Mr. Backward. What other crazy things does he do? Does he wear a suit to bed and pajamas to work? Does he eat dinner in the morning and breakfast at night? It’s all up to you. You decide what silly things you want Mr. Backward to do and then write them down.

How one more reverse/backward poem? This one will be about a person who does everything in reverse. But strangest of all, she also talks backward!

This one is a little harder than the other two, because every line in the poem is backward. But let’s have a look at it first, and then I’ll show you how it’s done.

Betty Backward is name my.

Reverse in but speak I.

Crazy I’m think just might you

Converse I how hear to.

Not only is this poem about a person who is a little bit backward, everything she says is completely backward as well. If you read each line backward, you will discover a whole new poem!

So how do you write a poem like this? It’s actually easier than it looks. First you write a normal poem, and then you reverse the lines. There’s just one more rule: Because the poem needs to rhyme after it’s reversed, you also need to rhyme the first words of your lines. The first words of your lines will end up being the last words when your poem is reversed.

Let’s add another stanza to the poem about Backward Betty, and I’ll show you how to do it. First let’s write it forward, here’s the first line of the new stanza.

No one understands me.

Notice that the first word of this line is “no.” That means our next line needs to begin with a word that rhymes with “no.” Let’s try “so.”

So they think I’m strange.

Now let’s add two more lines with rhyming first words, where the last word of the second line rhymes with “strange.”

My speech may be confusing,

but I know I’ll never change.

Lastly, let’s put it all together and then reverse it. Here are both stanzas together.

Betty Backward is name my.

Reverse in but speak I.

Crazy I’m think just might you

Converse I how hear to.

Me understands one no.

Strange I’m think they so.

But confusing be may speech my.

Change never I’ll know I.

Now that you know how to do it, see if you can add one or two more stanzas of your own to Backward Betty. Have fun!

Tongue Twisters

What’s a tongue twister? A tongue twister is a poem that is nearly impossible to read without tripping up as you recite it. You’ve probably heard of “rubber baby buggy bumpers” or “she sells seashells by the seashore.” As they say, “try to say that three times fast.” Chances are your tongue won’t be able to do it.

So how do you write a tongue twister? How do you write a poem that is guaranteed to trip up all but the most careful reader? It’s not that hard, actually. All you need to do is make a list of words that sound a lot alike and then putting them together.

For example, let’s take “sea sells seashells by the seashore” and see if we can’t come up with a few more words that sound like “she sells” and “seashells.” How about these:

- Smells

- Sails

- Sure

- Cellars

Next, why don’t we give this girl a name? Let’s call her Shelley Sellers. So where, by the seashore, would Shelley Sellers sell her shells? How about Shelley’s Seashell Cellars? So here we go.

Shelley Sellers sells her shells

at Shelley’s Seashell Cellars.

Now we know who she is and where she sells her shells, but who buys them? Who is Shelley selling shells to? Let’s look at our list of words. Smelly rhymes with Shelley, and dwellers rhymes with Sellers, so what if she sells her shells to smelly seashore dwellers?

She sells shells (and she sure sells!)

to smelly seashore dwellers.

What makes a tongue twister hard to say is the fact that it has lots of similar, but slightly different sounds. For example, “She sells seashells by the seashore” has a lot of “s” and “sh” sounds, as well as both long and short “e” sounds. In fact, “she sells” is the reverse of “seashells” in terms of the sounds. This makes it somewhat confusing to say; it trips up the tongue.

If you keep going with this idea of lots of “s” and “sh” sounds, you could create an entire tongue twister poem, perhaps something like this:

Smelly dwellers shop the sales

at Shelley’s seashell store.

Salty sailors stop their ships

for seashells by the shore.

Shelley’s shop, a shabby shack,

so sandy, salty, smelly,

still sells shells despite the smells;

a swell shell shop for Shelley.

But “s” and “sh” aren’t the only sounds you could repeat a lot to trip up the reader’s tongue. Using lots of words with “b” and “g” sounds, you might write a poem about someone named “Gabby” who bought a “beagle” that “begged” for “bagels.”

Gabby bought a baby beagle

At the beagle baby store.

Gabby gave her beagle kibble

But he begged for bagels more.

Or maybe with “s” and “z” sounds, you could write about someone named “Suzie” who like to “snooze” in “zoos.”

Suzie likes to snooze in zoos.

Suzie chooses zoos to snooze.

Or with “sh” and “ch” sounds, you might write about a “ship shop” that sells “shrimp ships” and a “chip shop” that sells “shrimp chips.”

Slim Sam’s Ship Shop

sells Sam’s shrimp ships.

Trim Tom’s Chip Shop

sells Tom’s shrimp chips.

See what I mean? Now it’s your turn. See if you can come up with a line or two that are particularly hard to say, make them rhyme, and you’ve got a tongue twister poem!

Repetition

Repetition means repeating words, phrases, lines, or entire stanzas in a poem. Using repetition in a poem can make it easier to read and remember.

One of the easiest ways to use repetition in a poem is to repeat the first words of every line or every other line. For example, you might start each line with something like, “When I was young…” or “Have you ever seen…” or “I hope I never…” or “I wish that I…”

Long before I became a poet, way back when I was in college, one of my teachers asked the class to write a repetition poem, and this is what I turned in:

Once I was a queen bee, but I had a case of hives.

Once I was a golf ball. That was how I learned to drive.

Once I was an ocean. I liked waving at the beach.

Once I was an apple. I was pretty as a peach.

Once I was a jellyfish, until I had to jam.

Once I was a cracker, and I only weighed a gram.

Once I was a cornfield, getting lost inside the maze.

Once I was I forest. Now I’m pining for those days.

I’ll admit it’s pretty silly. Each begins with me imagining something ridiculous that I used to be, and ends with a pun of some sort, just as we discussed in Chapter 4.

Why don’t you try picking a few words and using them at the beginning of each line of a poem?

You can also repeat entire sentences throughout a poem. For example, imagine a person who thinks they are beautiful, though maybe they are not quite as pretty as they think. You might then use the line, “I think I’m rather beautiful” throughout the poem, like this:

I think I’m rather beautiful.

My head is flat and square.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

My ears grow curly hair.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

I’ve wrinkly purple skin.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

I’ve mushrooms on my chin.

Can you think of a few more ways to describe this person? What about the feet? Are they size 23? The knees? The hands? The lips? Think about it and then add another stanza. Or two. Or three. When you are all done describing this unusual person, find a way to end your poem, perhaps like this.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

My nose is long and blue.

I think I’m rather beautiful.

I hope you think so too.

You might notice this is also a “backward” poem, because this person is the opposite of what they think they are. Remember what I said earlier: any one funny poem may contain features of several different types.

List Poems

Many famous poets, including authors such as Shel Silverstein, Jack Prelutsky, and even Dr. Seuss have written funny list poems. A list poem usually consists of three parts, a beginning, an ending, and a long list of things in the middle.

For example, take a look at my poem “My Parents Sent Me to the Store.”

My parents sent me to the store

to buy a loaf of bread.

I came home with a puppy

and a parakeet instead.

I came home with a guinea pig,

a hamster and a cat,

a turtle and a lizard

and a friendly little rat.

I also had a monkey

and a mongoose and a mouse.

Those animals went crazy when

I brought them in the house.

They barked and yelped and hissed

and chased my family out the door.

My parents never let me

do the shopping anymore.

You’ll see that the first two lines are the beginning, the last six lines are the ending, and everything else is the list in the middle.

One way to get started with list poems is to take a list poem that someone else has written and see if you can add another stanza or two to the list in the middle. Since “My Parents Sent Me to the Store” is all about animals this child brought home, and each stanza has two rhyming words, you would just need to think of two more animals that rhyme. For example, you might rhyme fox and ox, or goose and moose, or eagle and beagle, or snail and whale, and you might come up with something like this:

I came home with a goldfish,

and a guppy, and a goose,

an eagle and a beagle

and a mammoth and a moose.

You can also write a list poem from scratch by following these steps:

- Decide what your list will include. Foods? Sports? Games? Musical instruments? Clothes?

- Find as many rhyming words as you can for your list. For example, if you were writing a list poem about foods, you might rhyme cake/steak, cheese/peas, potatoes/tomatoes, beans/greens, and so on.

- Think of a beginning and an ending for your list poem.

- Start writing.

Today I decided to write a list poem about clothes. I can think of rhymes like shirt/skirt, boots/suits, bows/hose, caps/wraps, and so on. Now I just need a beginning and an ending and I can start working on my list. How’s this?

Wherever Dressy Bessie goes,

she always wears too many clothes.

That sounds pretty good to me. Now I can make a list of all the clothes she wears, like twelve pairs of slacks, eighteen shirts, thirty-seven hats, and so forth. For an ending, I’ll need to think of what would happy to Dressy Bessie with all these clothes on. Maybe she can’t stand up any longer, or she can’t squeeze through the door.

Now Bessie can’t fit through the door.

She never goes out anymore.

Now all I need is my list, like this:

Wherever Dressy Bessy goes,

she always wears too many clothes.

She puts on six or seven shirts,

eleven hats, and twenty skirts,

a half a dozen anoraks,

a pair, or two, or three of slacks.

She even wears eight pairs of boots,

and sixty-six seersucker suits.

Now Bessy can’t fit through the door.

She never goes out anymore.

Why don’t you see if you can add a few more lines to this poem. Perhaps you can use some of the rhymes I didn’t, like bows/hose or caps/wraps.

Or maybe you could come up with your own list poem with some rhyming foods, animals, or something else.

Updated Nursery Rhymes

Another popular way to write funny poems is to take old poems that you already know and change them to make them funnier. The easiest way to do this is with Mother Goose nursery rhymes. It only takes a few steps:

- Pick a nursery rhyme, such as Humpty Dumpty or Mary Had a Little Lamb.

- Find the words in the poem that rhyme.

- Change the rhymes to make them funnier.

Let’s take Humpty Dumpty as an example. This old nursery rhyme goes:

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall.

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall.

All the king’s horses and all the king’s men,

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

As you can see, “wall” rhymes with “fall” and “men” rhymes with “again.” But what if we put Humpty somewhere other than the wall? Maybe he sat in a tree, or on a cat, or on the moon. Then we might rhyme tree with bee, or cat with hat, or moon with June, and we might end up with something like this:

Humpty Dumpty sat in a tree.

Humpty Dumpty got stung by a bee.

He fell out and hit his head,

And now he thinks his name is Fred.

Or maybe something like this:

Humpty Dumpty went to the moon,

To eat in the restaurant they opened last June.

He said, “All the food is delicious up here.

I just wish the restaurant had more atmosphere.”

What about Mary Had a Little Lamb? If we changed it to make it funnier, we might end up with something like this:

Mary had a little yam,

with stuffing, gravy, pie and ham.

Now Mary isn’t any thinner.

Welcome to Thanksgiving dinner.

Now you try it. Pick your favorite nursery rhyme, locate the rhyming words, change them for something else, and come up with a brand-new funny poem of your own.

More, More, More!

In this chapter, you learned a few different ways to write funny poems, but there are many, many more. In the next chapter, we will look at some of the traditional forms of poetry that can be used to create funny poems, including limericks, clerihews, and even funny haikus.

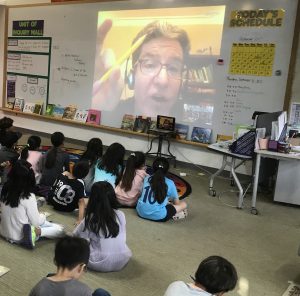

Kenn Nesbitt, former U.S. Children's Poet Laureate, is celebrated for blending humor and heart in his poetry for children. Known for books such as "My Cat Knows Karate" and "Revenge of the Lunch Ladies," he captivates young readers globally.

Latest posts by Kenn Nesbitt

(see all)

For several years now I have been doing live, interactive webinars in conjunction with

For several years now I have been doing live, interactive webinars in conjunction with